On this date, August 24, 2014, the Osborne County Hall of Fame is pleased to present to the world the fifth and last of the members of the OCHF Class of 2014:

He has been called one of the greatest college football coaches of all time. He forever changed both college and professional football with his invention of the I-Formation and sowing the seeds for the West Coast Offense. And, he was born in Downs, Osborne County, Kansas. We welcome Francis Albert Schmidt to the Osborne County Hall of Fame.

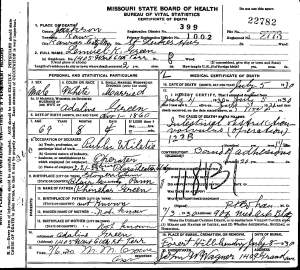

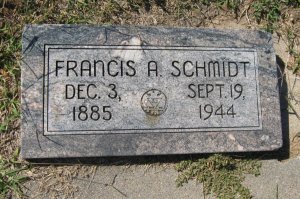

Francis was indeed born in Downs on December 3, 1885. His father, Francis W. Schmidt, was an itinerant studio photographer. His mother, Emma K. Mohrbacher, a native Kansan. Francis and Emma would have one other child, a daughter, Katherine.

As a photographer the elder Francis stayed in a particular location for only a few years before moving on. After stops in Oklahoma, Arkansas, Texas, and Kansas, the family was living in Fairbury, Nebraska, when young Francis graduated from Fairbury High School in May 1903. A year later he enrolled in the University of Nebraska.

Francis participated in football, baseball, basketball, track and the cadet band at the University of Nebraska while earning a law degree in just three years, graduating in 1907. Due to his mother having a serious illness Francis put aside his law career and helped his father with the photography studio in Arkansas City, Kansas, and taking care of his mother, who died later that summer. He helped the local high school football team that fall, as they had no coach, and even coached the boys and girls high school basketball teams that winter, leading the girls (with his sister Katherine as the center) to an undefeated season and the Kansas state championship.

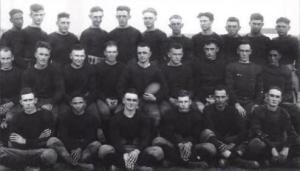

For the 1908-1909 school year Francis was offered the position of high school athletic director. He held it until the spring of 1916 and continued to coach both football and basketball with amazing success. Then Henry Kendall College in Tulsa Oklahoma, hired him to be their football, basketball, and baseball head coach. His time there was interrupted by World War I, through which he served as a military instructor in bayonet, rising to the rank of captain. After the war he returned to Henry Kendall College (later renamed the University of Tulsa) and his 1919 football team roared its way to a record of 8-0-1. In the 1919 season Kendall defeated the vaunted Oklahoma Sooners, but a 7-7 tie with Oklahoma A&M that year prevented a perfect season. Francis became known as “Close the Gates of Mercy” Schmidt because of his team’s tendency to run up the score on inferior teams. During Schmidt’s three years at Kendall the football team won two conference championships as they defeated Oklahoma Baptist 152-0, St. Gregory 121-0, and Northeast Oklahoma 151-0, as well as a 92-0 defeat of East Central Oklahoma and 10 other victories by more than 60 points each time.

It was around this time that Francis married Evelyn Keesee. The couple would have no children.

Francis was then hired to be the head football, basketball, and baseball coach at the University of Arkansas , where he compiled a 42-20-3 record in football for the Razorbacks from 1922-1928 and a 113-22 record in basketball – winning four Southwest Conference Championships in basketball in 1926, 1927, 1928, and 1929 – as the school’s first-ever such coach.

From Arkansas Francis went on to become the head football coach at Texas Christian University (TCU) where he won nearly 85% of his games. Schmidt did everything to extremes, including recruiting. He refereed high-school football games, but spent much of his time telling select players why they should commit to TCU in the days before athletic scholarships. In five years at Texas Christian, 1929-1934, Francis compiled a 46-6-5 record and won two Southwest Conference championships.

At this time Ohio State University was a backwater in terms of major college football. Desperate to build a winning program, they took a chance on Schmidt, their third choice for the head coaching job. At 6 feet 2 and 200 pounds, Schmidt was a large man with a prominent nose and distinctive drawl. Schmidt used his World War One bayonet drill instructor experience in running his practices. This, together with a loud, raucous and colorful approach to the English language, created an imposing character the likes of which had never been heard on the serene and conservative Ohio State campus. “He was Foghorn Leghorn in a three-piece suit and bow tie”, recalled one former player.

Schmidt arrived in Columbus on February 28, 1934. Within hours, the coach had distinguished alumni, faculty members and reporters on their hands and knees combing the carpets of a hotel conference room. Asked for his offensive strategies, the Downs, Kansas native dropped to the floor, pulled nickels and dimes from his pockets and diagramed his innovative visions for the Buckeyes. The Columbus Dispatch columnist Ed Penisten depicted the bizarre scene: “He was a zealot, full of excitement, confidence and quirks. Converts began to join him on the floor including OSU assistant football coaches. He moved the nickels and dimes around like a kaleidoscope.”

Francis soon proved his genius for offensive football. In his first year at Ohio State he stunned the opposition by displaying – in the same game – the single wing, double wing, short punt and, for the first time ever, his own invention: the I-formation. He used reverses, double reverses and spinners, and his Buckeyes of the mid-nineteen thirties were the most lateral-pass conscience team anyone had ever witnessed. He threw laterals, and then laterals off of laterals downfield, and it was not unusual for three men to handle the ball behind the line of scrimmage. In his first two years he got touchdowns in such bunches that Ohio State immediately was dubbed “The Scarlet Scourge.” He was a bow-tied, tobacco-chewing, hawk-faced, white-haired, profane practitioner of the football arts – modern football’s first roaring madman on the practice field and the sidelines, and so completely zonked out on football that legend ties him to the greatest football story of the twentieth century:

So caught up was Francis in his diagrams and charts that there was hardly a waking moment when he wasn’t furiously scratching away at them. He took his car into a filling station for an oil change but stayed right in the car while the mechanics hoisted it high above the subterranean oil pit to do their work. Francis Schmidt, immersed in his X’s and O’s, simply forgot where he was. For some reason he decided to get out of the car, still concentrating on his diagram. He opened the door on the driver’s side and stepped out into the void, which ended eight feet south of him in the pit. He refused to explain the limp which he carried with him to practice that day.

At Francis’ first football banquet after a sensational first season capped by a glorious 34-0 shellacking of Michigan, Schmidt bawled forth two classic and historic comments. “Let’s not always be called Buckeyes,” he brayed. “After all, that’s just some kind of nut, and we ain’t nuts here. It would be nice if you guys in the press out there would call us “Bucks” once in a while. That’s a helluva fine animal, you know.” Ringing applause. And then:

“As for Michigan – Well, shucks, I guess you’ve all discovered they put their pants on one leg at a time just like everybody else.” Bedlam. It was the apparently the first time the homely Texas line had ever been uttered in public and it swept the nation. It also launched a “Pants Club” at Ohio State; ever since 1934 each player and a key booster who is part of a victory over Michigan is awarded a tiny little golden replica of a pair of football pants.

The Ohio State Buckeyes became a national sensation in 1935. They won their first four games, setting up an undefeated showdown against Notre Dame. The game attracted a capacity crowd of 81,018 and has been often called “The Game of the Century.” The Buckeyes surged to a 13-0 lead, but their advantage vanished in the fourth quarter. The Irish scored twice in the final two minutes to beat the Buckeyes 18-13. The Buckeyes regrouped and won their final three games, including a 38-0 pasting of Michigan, to win a share of the Big Ten title – their first in 15 years.

Schmidt, however, was haunted by the Notre Dame loss. It was the first in a string of big-game losses, and critics started to question whether his reliance on laterals, shovel passes and trick plays worked against top-quality opponents. Schmidt never worried about “getting back to basics,” because he didn’t stress them. His long practices were light on fundamentals such as blocking and tackling. Perhaps fueled by paranoia, Schmidt didn’t delegate authority, which often reduced his assistants to spectators at practice. He kept the master playbook locked away; players’ copies contained only their specific assignments and no hint at what their 10 teammates were doing. Among his shortcomings, Schmidt never understood the importance of mentorship and discipline. In Schmidt’s last seasons, key players became academically ineligible; others showed up late to practices. Team morale suffered. After the 1940 season in which the Buckeyes won four games and lost four, Schmidt resigned amidst heavy criticism from both fans and the administration. His total win-loss-tie record with the Buckeyes was 39-16-1 with two Big Ten championships.

The only position that Francis could then find as a head coach was at the University of Idaho. In 1941 his team posted a 4-5 record, and in 1942 they finished 3-6-1. Then the school suspended football because of World War II.

Francis never coached again, ending with a college coaching record of 158-57-11. He stayed on campus to help condition service trainees, but barely a year later he fell into a long illness and died at St. Luke’s Hospital in Spokane, Washington, on September 19, 1944, at the age of 58. Francis was laid to rest beside his parents in the Riverview Cemetery at Arkansas City, Cowley County, Kansas.

The legacy of Schmidt has endured thanks to Sid Gillman, a Pro Football Hall of Fame coach who was a Buckeye end in the early 1930s and an assistant under Schmidt. Gillman is considered the father of the modern passing offense, and specifically the West Coast Offense which he used as a head coach. He always gave credit to Francis Schmidt that the principles of that offense were based on what he was taught by Schmidt. Gillman’s teachings had significant impact on the careers of later National Football League icons such as Al Davis and Bill Walsh.

Francis Schmidt’s imprint on the collegiate game remains well into the modern era as well. In the 2006 Fiesta Bowl, Boise State used three trick plays – a hook and lateral, Statue of Liberty, and wide-receiver pass – to stun Oklahoma 43-42. Schmidt had made all three plays famous while using them at Ohio State.

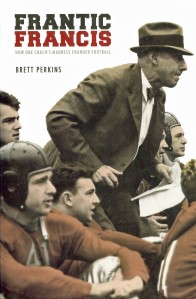

75 years after Schmidt coached his first game at Ohio State, a new book profiling his life was published. Frantic Francis, written by Brett Perkins (University of Nebraska Press, 2009) examined not only his career but also his effect on the modern game. In 2019 he was named by the sports channel ESPN as one of the 150 greatest coaches of all time in the first 150 years of college football.

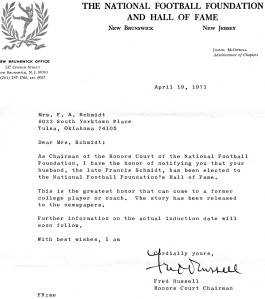

Francis Albert Schmidt was elected to the College Football Hall of Fame in 1971. He is also a member of the Halls of Fame at Nebraska, Tulsa, Arkansas, Texas Christian, and Ohio State. And now he is the newest member of the Osborne County Hall of Fame.

SOURCES: Barbara Wyche; Frantic Francis, written by Brett Perkins, (University of Nebraska Press, 2009); Columbus Dispatch, Thursday, September 3, 2009; Topeka Daily Capital, May 16, 2012; The Spokesman-Review, November 6, 2009; University of Arkansas Athletics Hall of Fame; University of Tulsa Athletics Hall of Fame; College Football Hall of Fame.