“There were three great types in the West: Buffalo Bill, hunter and scout; Wild Bill Hickock, gunman; and Buffalo Jones, the preserver, who brought living things wherever he went.” – Zane Grey.

“There were three great types in the West: Buffalo Bill, hunter and scout; Wild Bill Hickock, gunman; and Buffalo Jones, the preserver, who brought living things wherever he went.” – Zane Grey.

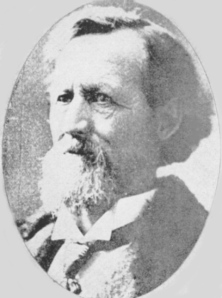

Considered one of the most celebrated characters of his time, Charles Jesse “Buffalo” Jones was born January 31, 1844, in Money Township, McLean County, Illinois. He was the third of twelve children born to Noah and Jane (Munden) Jones on the family farm, where Abraham Lincoln was a frequent visitor and family friend. For the first seventeen years of his life Charles helped with the farm work. In 1862 he entered Illinois Wesleyan University, but typhoid fever forced him to give up his studies after two years. He thought to try his luck out West and so in 1866 he found himself in Troy, Kansas.

At Troy Charles started a nursery and built a stone house. On January 20, 1869, he was married at Troy to Martha J. Walton. Their union produced six children, four of whom are known: Charles, William, Jessie, and Olive. While living in Troy, Charles took his first trip out to the buffalo range to hunt the American bison. Intrigued by the great beasts and the money to be earned for their hides, he moved his family west in order to be closer to the range. On January 1, 1872, the Jones family arrived in Osborne County, Kansas, settling on a homestead in Section 19 of Tilden Township.

Anybody Know Him?

“The Kansas City Times of October 7th contained a three-column writeup of Charles J. Jones, known to the world as ‘Buffalo’ Jones. Jones died in Topeka some two weeks ago. The articles says . . . Jones came to Kansas in 1866, going first to Doniphan County, but four years later settled on a claim in Osborne County, his home standing on the South Fork of the Solomon River . . . If ‘Buffalo’ Jones ever lived in Osborne County the editor of the Farmer never heard of it . . . If any of the old-timers know anything about ‘Buffalo’ Jones ever having lived here they will help out on a historical question by speaking up right now. If Osborne County was ever the home of so famous a character as ‘Buffalo’ Jones the county is entitled to the honor and credit of it.” — Osborne County Farmer, October 16, 1919.

Yes, He Lived Here

“The Farmer’s article last week asking if anyone knew ‘Buffalo’ Jones when he lived in Osborne County soon brought forth conclusive proof that he was once a resident of Osborne County . . . C. A. Kalbfleisch, who now lives over at Harlan, writes us as follows regarding the Jones affair: ‘I noticed your article in the Farmer of even date in regards to ‘Buffalo’ Jones and can tell you exactly where his homestead was. It is located one mile south and one and a quarter west of Bloomington in TildenTownship. In 1900 I bought this place from D. A. Rowles and among the papers turned over to me was the original patent from the government, dated, I think, 1874, and signed by U. S. Grant, president, to Charles J. Jones. I talked at the time with Frank Stafford and he said this was ‘Buffalo’ Jones . . . .’

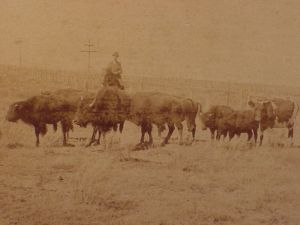

L. F. Storer of BethanyTownship tells us he knew ‘Buffalo’ Jones well. Jones taught a Sunday School class in Doniphan County and Mr. Storer was one of his pupils. He says Jones used to visit at the home of his father frequently and they were intimate friends. Jones was not much of a hunter here, but he did a lot of lassoing of buffalo. He trained several of them to work as oxen.

J. E. Hahn is another who remembers Jones well. Ed says his father often told him in later years of one of Jones’ hobbies. He claimed to have the plans and a marked map of the place where a great fortune was buried in one of the Sandwich Islands [Hawaii]. He wanted J. W. Hahn to go with him and secure the treasure. Jones, with all of his traveling in later years, evidently had forgotten all about that fortune, as history does not mention that he ever visited the Sandwich Islands.

John J. and Robert R. Hays knew ‘Buffalo’ Jones very well. John says Jones came here from Troy, Doniphan County, in 1872 and stayed here, he thinks, three or four years. His family was here that long, but after a year Jones used to be away a great deal on hunting trips or some other line of business. John says he was a good-natured fellow and very likable, but also very visionary.” — OsborneCounty Farmer, October 23, 1919.

In Osborne County Jones divided his time between hunting and farming. He started a nursery and served as Tilden Township’s justice of the peace. In 1874 Jones was appointed Osborne County Undersheriff. Often he was away on long hunting trips, where he learned by necessity the science and art of scouting. On the range they began to call him “Buffalo” Jones (though never to his face) to differentiate him from “Dirty-Face” Jones and “Wrong Wheel” Jones, who were both also on the range. In 1876 Jones had sold the homestead and settled his family in Sterling, Kansas. Three years later he became one of the four founders of Garden City, Kansas, where Jones started a ranch and proceeded to make his mark on the community. He was soon referred to as “Colonel” Jones, because, as he later put it in his autobiography, it was “the title awarded in the Old West when a man reached a certain level of popular esteem.” This may indeed be the case, as it was Jones who convinced the Santa Fe Railroad to establish a station at Garden City, and it was Jones who in 1885 completed a stone courthouse and presented it and the surrounding block to the county as a gift. He also served as the town’s first mayor and as Finney County’s first representative to the Kansas Legislature, where he worked alongside Hiram Bull, representative for Osborne County. Jones predicted Bull’s death by an angry tamed elk.

“A tame wild animal is the most dangerous of beasts. My old friend, Dick Rock, a great hunter and guide out of Idaho, laughed at my advice and got killed by one of his three-year-old bulls. I told him they knew him just well enough to kill him, and they did.

Same with General Hiram Bull, a member of the Kansas Legislature, and two cowboys who went into a corral to tie up a tame elk at the wrong time . . . They had not studied animals as I had. That tame elk killed all of them . . . You see, a wild animal must learn to respect a man.” — Buffalo Jones in his autobiography Buffalo Jones: Forty Years of Adventure (1899).

By 1886 Jones had realized that the wholesale slaughter of the buffalo would lead to their eventual extinction and regretted his role in it. Between 1886 and 1889 he made four trips to the Texas panhandle to capture buffalo calves and turn them loose on his ranch. Within three years he had assembled a herd of over one hundred and fifty animals; at the time the only other herd left in the continental United States was sheltered in Yellowstone National Park – a herd of only two hundred and fifty head. In 1901 the two herds were merged, and from this new herd are descended most of the American bison in existence today. Jones also purchased other private herds, including one from Canada that caused considerable controversy. His exploits earned him a world-wide reputation and he was hailed everywhere as the Preserver of the American Bison. In 1890 he started a second ranch near McCook, Nebraska, on which part of his enlarged herd were protected. While some critics denounced his capturing buffalo as hastening their end forever as wild animals, he always defended himself by pointing out that if he did not do it, then the buffalo hunters would – and they would do all they could not to keep them alive. In 1891 Jones made a trip to England with ten full grown buffalo. The animals were not entirely sure about the idea of traveling on ship, but in the end they were delivered to the London Zoological Gardens and Jones became the talk of Europe after he presented the Prince of Wales with a magnificent buffalo robe.

But with all this activity Jones had overextended his dwindling finances and he lost everything in the end, including both ranches. His family went back to Troy to live with his in-laws while he sought to reestablish himself. In 1893 Jones made the Cherokee Strip run to Oklahoma Territory and secured land near Perry. He then became sergeant-at-arms of the Oklahoma Legislature. After a while he was reported to be on the Gulf Coast of Texas, promoting a railroad from Beaumont to Fort Bolivar on Galveston Bay. Then he hit on a new scheme that once again brought him national attention – he would lead an expedition into the Arctic Circle that would lasso and capture musk oxen and bring them back alive; something that had never been achieved before.

On June 12, 1897, he set out. At Fort Smith on the Slave River in Alberta, Canada, he took on a partner, John Shea, a Scotch trapper and trader, and attempted to locate and snare the wild oxen. But blizzards and other rough weather thwarted his plans; in the end they did manage to capture five calves, but the local Indians slit their throats for a native ritual. The discouraged partners gave up the whole venture and Jones started on the way back home. The following year he briefly joined the Alaska Gold Rush. His partner Shea went on to Dawson in the Yukon Territory while Jones thought it was high time to get back to his family and boarding a steamer set sail for Seattle and the United States.

Jones reunited with his family back in Troy on October 8, 1898, after five years of separation. With Colonel Henry Inman he penned his autobiography, Buffalo Jones: Forty Years of Adventure, which appeared in print in 1899. In July 1902 President Theodore Roosevelt appointed him game warden of Yellowstone National Park, a position he held until September 1905 when he resigned in a dispute with the U.S. Army, who were then in charge of the Park. The next year he established a ranch along the northern rim of the Grand Canyon in Arizona Territory. He had once before tried to cross domestic cattle with the buffalo, which he dubbed “the cattalo,” and had failed, and here he tried again. But the cattalo never became popular. It was also here that a dentist from New York City, Zane Grey, visited Jones in the spring of 1907 in hopes that his health would improve. Together they roped and relocated mountain lions and Grey wrote his first book, Last of the Plainsmen, with Jones as the hero.

“Buffalo Jones was great in all those remarkable qualities common to the men who opened up the West. Courage, endurance, determination, hardihood, were developed in him to the highest degree. No doubt something of Buffalo Jones crept unconsciously into all the great fiction characters I have created.” — Zane Grey.

In 1910 Jones made his first trip to Africa to rope wild animals. A silent film and lecture tour on the trip were national sensations and his previous exploits were also given much publicity. Four years later, at the age of seventy, Jones made a second trip to Africa, this time to rope and capture gorillas. On this trip Jones contracted jungle fever and suffered a severe heart attack. His health never recovered and he spent his last years in Topeka, Kansas, where he died October 2, 1919.

Charles “Buffalo” Jones was buried in the family plot in the Valley View Cemetery at Garden City. He never fitted in with the stereotype of the westerner found in dime novels or in movies and television – he did not gamble or use coffee, tea, tobacco, or liquor – and so his legendary life has faded from the American consciousness. In 1982 his successful preservation efforts to save the American bison earned him a posthumous induction into the National Buffalo Association’s Buffalo Hall of Fame. His character, courage, and indomitable spirit as a child of the American West has also earned him a permanent place in the Osborne County Hall of Fame.